Deep in Paradise

Created January 8, 2023

Last Modified July 25, 2023

This is a short story about some of the tensions I grew up

with in

the forties and fifties. I hope you enjoy it and maybe benefit from it.

the forties and fifties. I hope you enjoy it and maybe benefit from it.

“A slice of apple pie, please.” “I’ll have the same, thanks. And coffee.” Dennis

and Edgar were sitting at the counter in the small restaurant on Brush Street

in Paradise Valley. The Detroit eatery served the best deep-dish apple pie in

the nation. Dennis and Edgar both lived on Farrand Park Street in Highland

Park, an affluent neighborhood, and they lived privileged lives to prove it.

Despite their poor assessment of Blacks, especially Black men, Dennis and Edgar

were both

somehow haunted by a lurking feeling that they might well be wrong. That they

were inferior, not those they stigmatized. They attended an integrated high

school. They were accustomed to being among Blacks in class and out. Never had

either one had reason to feel threatened. There was conflict in their school,

but it was not constant, and it was likely to be between kids of any color or

ethnicity. Their school comprised many different sorts: Middle Eastern,

Caribbean, Central American, South American, African American, from various African

cultures, from various Asian cultures, and Whites from various European countries.

Many of the Blacks came from families that had been in North America for

centuries, far longer than most of the Whites, and surpassed only by Native

Americans, of which there were a few in their school as well. The gang culture

found in so many neighborhoods of large American cities was not to be found in

Highland Park. The fights that sometimes occurred in their school hallways were

always between just two, and never ended in serious injury, despite the rare

appearance of knives. Yet Dennis and Edgar spent most of their days afraid, and

they were not sure what they were afraid of.

Fear must be dealt with in some manner, and far too often it was expressed with hatred. Dennis and Edgar were aware of the hatred but not the fear. They dealt with fear not just with projected hatred but also with denial. They used this denial as a rationalization of their need to eat apple pie in Paradise Valley. This time their worst fears seemed to be realized. Just as they began eating their pie, in through the front door came two teen-aged Black kids. Males. At first the kids just sat down at the counter a few seats away from Dennis and Edgar. They too, ordered apple pie, but they were most decidedly impressed by the woman who brought them their orders. That did not deter them from keeping an eye on the two White boys. They approached the White boys and asked, “Gotta cigarette?” Edgar was convinced his life was about to end, but with shaking hands he retrieved a pack of Chesterfields and each of the other two boys took one. Then one of the two Blacks asked if Dennis and Edgar could give them a ride home. “Why are you shaking like that?” Edgar now knew for sure that their bodies would be found in the morning, but he made no reply. Dennis offered, “Sure, no problem.” Edgar’s heart sank in his chest, but he knew he had no choice but to go along with Dennis.

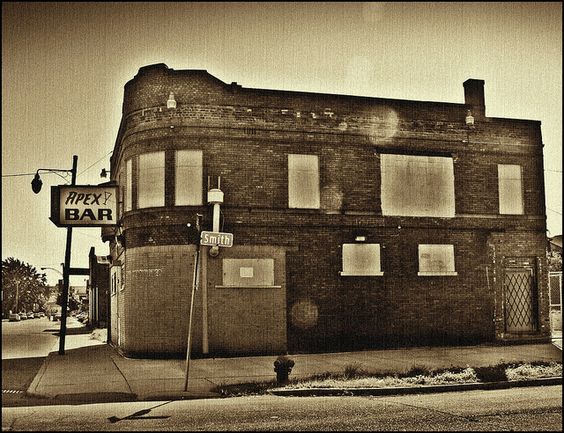

The four of them left the restaurant and got into Edgar’s car, a green customized ’50 Ford Coupe. “Where to?” said Edgar. “Turn left and go down to John R, then hang another left.” With Edgar visibly trembling, he followed the instructions. “Now go down to Smith Street, turn left, and let us off at the third house on the right.” When they got to Smith Street, the Black kids got out of the car. “Hey, thanks a lot man. Really appreciate the lift.”

Edgar was nearly in tears, and he could not believe his life was spared. “I dunno, they seemed friendly to me,” said Dennis. “Yeah, we were just lucky,” returned Edgar. “Lucky or not, let’s go home. Turn onto Brush here and head North back to HP.” “Yeah. OK.” As they moved north on Brush Street, they saw that the neighborhoods slowly included more Whites, and both, especially Edgar, felt more comfortable with each block.

It seems that no matter how many positive experiences the pair had with “the other” they persisted in their negative attitude about Blacks. The next week in HP High they related their “incident” to Charlene, a savvy White senior. “You’re just thinking and saying what your racist parents taught you.” “Whadda you mean? My Mom and Dad always say that they’re colorblind,” cried Dennis. “Yeah, sure. Saying they’re colorblind means they think they have the right to feel superior without being explicit,” returned Charlene. “Colorblind means that White is the default,” she added. Dennis claimed that his parents had never talked bad about Blacks. “Well, what do you think?” asked Charlene. “Me? I know for a fact that they’re stupid and lazy!” offered Dennis. “How about you?” asked Charlene, turning to Edgar. “I’m with Dennis. I know that Whites have always used colored people for their dirty jobs. It used to be that we had slavery because that’s all niggers are good for.” That the ‘n’ word fell so easily from his lips revealed a lot.

“Why do you think so many Blacks are varsity football and basketball players?” Charlene was trying to find a way to get through to Dennis and Edgar, so far with little success. “You don’ gotta be smart to play basketball or football” Edgar maintained. Charlene groaned audibly. She didn’t like to use false racial stereotypes, but sometimes they could be helpful. Dennis said, “Blacks are all just brutes, anyway.” Charlene groaned once again. “So why did you go to that restaurant?” Dennis replied “Blacks have been cooking for Whites for a long time, so there are some pretty good cooks. Look at the Aunt Jemima boxes of pancake mix. And how about Uncle Ben’s Rice?”

Charlene knew that both Dennis and Edgar heard this stuff in church. Dennis was Catholic, Edgar went to an evangelical church. Each of these religions found Whites superior in their own way. Evangelicals believed that anyone who accepted Christ as their savior would go to Heaven. But only White people. ‘Coloreds’ were going to Hell because the Bible said so. The ideas about Blacks that they learned in their respective churches were never explicit. For that, they listened to the radio. Yet the churches, both of them, made things very clear in an indirect sort of way. All the images of supposedly saintly figures were of Whites, with flowing blond hair and beards. Both males and females were portrayed as White blonds. Even in the fifties there were evangelists saying that communism was attempting to destroy Christianity, and communism advocated civil rights for all, so that had to prove something. And there were some in the government who had it right. The guy who had the communists pegged was Senator Joe McCarthy, but he had died that year. Anyway, the government was not the place to go to. They did have Norman Vincent Peale, and especially Billy Graham. Graham said that Christians didn’t have to do anything for the ‘coloreds,’ because the corrupt Federal Government was taking care of that, giving out welfare to lazy Blacks, and so on.

“So, why did you go to that Brush Street restaurant?” Charlene asked. “To show that we ain’t scared of them” said Edgar. “Yeah, you was plenty scared. You were shakin’ like a leaf,” Dennis interjected. “But I was there,” said Edgar. “Well, we won’t go again. I’ve had enough of that crap,” returned Dennis.

One day, soon after the incident in Paradise Valley, Dennis went to the Highland Park Post Office. There he encountered a table set up in front of the Office, which table was covered with pamphlets and even books dealing with right-wing Christian advocacy of anti-communism, and with it fervent anti-civil rights. “I’m not interested in communism; I’m trying to keep Blacks in their place. And they know their place. It’s just that some are uppity.”

But it could not be denied that there was plenty of racism in 1950s Highland Park. The high school had more than a few Black students. Some, not all, were friendly with some, not all, White students. Roger and Earl were two such White kids, and Miles and Charlie were two such Black kids. The four of them were pretty good friends, not close friends, but friends. They thought the way around the habitual attitude of White supremacy was simple. Act as though that sense did not exist. The four could usually be found shooting hoops on the outside court behind the school. They socialized together. Each of the four at one time or another invited the other three to have dinner at his house. They went to dances together; they went to sports events together. Unfortunately, interracial dating was risky, although Earl had a huge crush on one of Miles’ sisters.

At the other extreme from those four friends, two Black and two White, were White students who wanted nothing more than to bar Black students and other students of color entirely. They said segregation was the best way to have racial peace. This alleged desire for racial peace didn’t prevent some of them from forming groups that excluded Blacks and other people of color from participation. Much was claimed by these groups about how inferior people of color were. Guy and Little Joe were confident that their group was the best of them all. It emanated from their strong devotion to Christianity, but it was their kind of Christianity. Their group, which they called HP Leaders, held that anyone not White (according to their lights) was inferior, and the Leaders were therefore entitled to power and control over everybody else. Only White males were members. If their families held property or had large financial assets, they could become Leaders of the Leaders. Guy and Little Joe often went to Palmer Park, especially to the picnic benches deep in the park.

Little Joe was not very little. He stood over six feet tall. Guy was a couple of inches shorter. Supposedly they were Christians, but they didn’t act that way. For starters, they didn’t like the idea of Black kids hanging out in Palmer Park. Roger and Earl had been going to Palmer Park for years. Charlie and Miles learned to skate there, and it was their first time in the park.

Earl had a sister, June Ann, a couple of years older than Earl. June Ann taught the four friends how to ice skate one winter. In the summer Ford Field was a sports field, with spaces for all kinds of warm weather sports. In winter, Ford Field was flooded, and the cold Michigan winters took care of the rest. Instead of skating at Ford Field, June Ann took the boys to Palmer Park that evening, just across Six Mile Road. There was a pond there that was maintained year ‘round, and in winter it was a great place to play hockey. Someone even set up a barrel jump, although real barrels weren’t used. Palmer Park was in the city of Detroit. Six Mile Road, also known as McNichols Avenue, formed the northern border of Highland Park.

Palmer Park was a forest in the middle of a metropolis. A good portion of it on the northeast corner, near Woodward Avenue, was set up for sports events, for the most part at a high school level. Most of the rest was effectively a forest. On one border, just outside the park, was a collection of large homes, mansions really, called Palmer Woods. Along another border was a golf course. Tucked away in a corner was a casting pond. No fish there but fly fishermen and bait casters alike used it for practice. Hidden away in the middle of the forest was a handball court. At the northern border was a stable, and the forest was laced with bridle trails. Riders presumed to be affluent were sometimes encountered on the trails. Adjacent to the stable was a substation of the Detroit Police Department. A narrow road through the park provided access to Six Mile Road for the police patrol cars.

Little known was a small clearing in the center of the park with a couple of picnic benches and a grill. There was no water. A well-worn trail gave access. It was a hangout for several groups of high school boys, White high school boys, that was a safe place to drink beer. For some reason the cops never seemed to come there.

In summer, the pond harbored a flock of mallard ducks, and sometimes a couple of Canada geese. These all migrated south when the weather turned cold. In time, the geese adapted and stuck around even in winter. They became a nuisance. In the late fifties, in winter, the park was largely unused, except for the pond, which nearly always froze for the season. A heated building at the edge of the pond was a convenient place for skaters to lace up their skates.

That winter evening, June Ann went with Earl, Miles, Charlie, and Roger to Palmer Park. Roger and Earl already knew how to skate. They were avid hockey players, playing pickup games in Palmer Park. Miles and Charlie were both athletic, and they took to ice skating with alacrity. They also realized that they had been missing out on a good thing because they didn’t know about the park. It became a habit for Roger, Charlie, Miles, and Earl to go to the picnic benches on summer nights.

For some unknown reason girls did not go to that part of the park. The same could not be said for Little Joe and Guy. They were regulars. They liked beer. So, one night the inevitable happened. Miles and Charlie were there one evening with Roger and Earl, just hanging out. Who showed up but Little Joe and Guy. When they saw Miles and Charlie, they were livid. No niggers in the park, bellowed Little Joe. Miles and Charlie didn’t want any trouble, so they started to move away, back toward Six Mile Road. Little Joe and Guy followed them; they did want trouble. Earl and Roger tried to get them to back off, to no avail.

As Miles and Charlie moved toward an exit from the park, a patrol car happened upon them as it was moving also toward Six Mile Road. The car stopped and two officers emerged, guns drawn. They had never seen Blacks in the park before, and they suspected the worst. Now Miles and Charlie were really in a panic. Running was the best thing they could think of.

“Stop!” said one of the cops. He fired and hit Miles in the back. Miles fell, and Charlie turned to help him. The cop fired again, and his bullet went into Charlie’s skull, killing him instantly. Little Joe and Guy split.

Miles was taken to a hospital, where he slowly recovered. Would that the same could happen to Charlie.

The next day, the newspapers reported that the cops claimed that they feared for their lives. In a masterpiece of illogic, if those kids were threatening, then why did they run? Both officers were put on administrative leave for about a month while the incident was “investigated.” Both were returned to regular duty.

How sad, and bitterly ironic, that Dennis and Edgar were terrified to be in Paradise Valley, thinking they would die, but it was two Black boys, Charlie and Miles, who were shot by White cops. A few years later, Paradise Valley, a major business center of Black Detroit in the middle of Black Bottom, fell victim to urban renewal, “redevelopment,” and the building of highways to help out with White flight, emanating from the endemic myth of White Male Superiority.